Practice Essentials

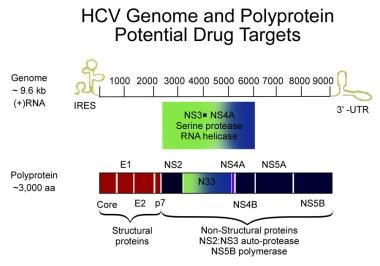

Hepatitis C is an infection caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV) that attacks the liver and leads to inflammation. The World Health Organization (WHO) [1] estimates that about 50 million people globally have chronic hepatitis C, with approximately 242,000 dying from this infection, primarily due to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (sixth most commonly diagnosed malignancy and third leading cause of cancer worldwide [2] ). Although direct-acting antiviral agents cure over 95% of individuals infected with HCV, no effective vaccine exists against hepatitis C. [1] The image below depicts the HCV genome.

Signs and symptoms

Initial symptoms of hepatitis C are often extrahepatic, most commonly involving the joints, muscle, and skin. Examples include the following:

-

Arthralgias

-

Paresthesias

-

Myalgias

-

Pruritus

-

Sicca syndrome

-

Sensory neuropathy

Symptoms characteristic of complications from advanced or decompensated liver disease are related to synthetic dysfunction and portal hypertension, such as the following:

-

Mental status changes (hepatic encephalopathy)

-

Ankle edema and abdominal distention (ascites)

-

Hematemesis or melena (variceal bleeding)

Physical findings usually are not abnormal until portal hypertension or decompensated liver disease develops. Signs in patients with decompensated liver disease include the following:

-

Hand signs: Palmar erythema, Dupuytren contracture, asterixis, leukonychia, clubbing

-

Head signs: Icteric sclera, temporal muscle wasting, enlarged parotid gland, cyanosis

-

Fetor hepaticus

-

Gynecomastia, small testes

-

Abdominal signs: Paraumbilical hernia, ascites, caput medusae, hepatosplenomegaly, abdominal bruit

-

Ankle edema

-

Scant body hair

-

Skin signs: Spider nevi, petechiae, excoriations due to pruritus

Other common extrahepatic manifestations include the following:

-

Cryoglobulinemia

-

Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis

-

Lichen planus

-

Keratoconjunctivitis sicca

-

Raynaud syndrome

-

Sjögren syndrome

-

Porphyria cutanea tarda

-

Necrotizing cutaneous vasculitis

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

General baseline studies in patients with suspected hepatitis C include the following:

-

Complete blood cell count with differential

-

Liver function tests, including levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase, albumin, and total and direct bilirubin

-

Calculated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)

-

Thyroid function studies

-

Screening tests for coinfection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or hepatitis B virus (HBV)

-

Screening for alcohol abuse, drug abuse, or depression

-

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) testing with hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) (to identify coinfection), as well as hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) and antibody against hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc) (for evidence of previous infection)

-

Serum pregnancy testing in women of childbearing age before initiating a treatment regimen that includes ribavirin or that includes direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) without ribavirin

Tests for detecting HCV infection include the following:

-

Hepatitis C antibody testing: Enzyme immunoassays (EIAs), rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs), and point-of-care tests (POCTs)

-

Qualitative and quantitative assays for HCV RNA (based on polymerase chain reaction [PCR] or transmission-mediated amplification [TMA])

-

HCV genotyping

-

Serologic testing (essential mixed cryoglobulinemia is a common finding)

Liver biopsy is not mandatory before treatment but may be helpful. Some restrict it to the following situations:

-

The diagnosis is uncertain.

-

Other coinfections or disease may be present.

-

The patient has normal liver enzyme levels and no extrahepatic manifestations.

-

The patient is immunocompromised.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Treatment of acute hepatitis C has rapidly evolved and continues to evolve. HCV infection has become a curable disease, although a vaccine does not yet exist.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Hepatitis C is a worldwide problem. The hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a major cause of both acute and chronic hepatitis. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates about 71 million people globally have chronic hepatitis C, with approximately 399,000 dying from this infection, primarily due to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). [1]

The prevalence of HCV infection varies throughout the world. For example, Frank et al reported in 2000 that Egypt had the highest number of reported infections, largely attributed to the use of contaminated parenteral antischistosomal therapy. [3] This led to a mean prevalence of 22% of HCV antibodies in persons living in Egypt.

In the United States, the incidence of acute HCV infection has sharply decreased during the past decade, but its prevalence remains high. According to US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates, 2.7-3.9 million people (most of whom were born from 1945 through 1965) in the United States have chronic hepatitis C which develops in approximately 75% of patients after acute infection. [4] This virus is the most common blood-borne pathogen in the United States [5] and a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, primarily through the development of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis; persons with chronic infection live an average of 2 decades less than healthy persons. [5]

Infection due to HCV accounts for 20% of all cases of acute hepatitis, an estimated 30,000 new acute infections, and 8,000-10,000 deaths each year in the United States. [6] HCV has rapidly surpassed human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) as a cause of death in the United States. An examination of nearly 22 million death records over 9 years revealed an HCV mortality rate of 4.58 deaths per 100,000 people per year and an HIV mortality rate of 4.16 deaths per 100,000 people. Almost 75% of HCV deaths occurred among adults between the ages of 45 and 64 years. [7]

Medical care costs associated with the treatment of HCV infection in the United States are high. Treatment with a 12-week regimen of HCV antiviral agents can cost up to $95,000. [8, 9] The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) remains up to $100,000 across all HCV genotypes and fibrosis stages. [8, 10] With an estimated 2.7-3.9 million people having chronic infection, the potential medication costs alone could range from $257 billion to $371 billion per year.

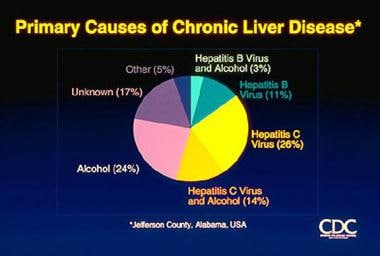

Because most patients infected with HCV have chronic liver disease, which can progress to cirrhosis and HCC, chronic infection with HCV is one of the most important causes of chronic liver disease (see the image below). The INSIGHT Study, which collected data both retrospectively (n = 1052) and prospectively (n = 1481) from 2533 newly diagnosed patients with hepatocellular cancer across 33 centers and 9 Asia-Pacific countries, found that hepatitis B was the most common risk factor in all countries except Japan, Australia, and New Zealand—the prevalence of hepatitis C and diabetes were more common in the latter 3 countries. [2]

According to a report by Davis et al, the most common indication for orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) in the United States. [11]

Hepatitis C. Causes of chronic liver disease. Courtesy of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Hepatitis C. Causes of chronic liver disease. Courtesy of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Most patients with acute and chronic infection are asymptomatic. Patients and healthcare providers may detect no indications of these conditions for long periods; however, chronic hepatitis C infection and chronic active hepatitis are slowly progressive diseases and result in severe morbidity in 20-30% of infected persons. Astute observation and integration of findings of extrahepatic symptoms, signs, and disease are often the first clues to the underlying HCV infection. [12]

Although acute HCV infection is usually mild, chronic hepatitis develops in at least 75% of patients. [13] (See Prognosis.) Although liver enzyme levels may be in the reference range, the presence of persistent HCV-RNA levels discloses chronic infection. Biopsy samples of the liver may reveal chronic liver disease. Cirrhosis develops in 20-50% of patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. Liver failure and HCC (11%-19%) can eventually result.

Pathophysiology

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a spherical, enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the family Flaviviridae, genus Flavivirus. Lauer and Walker reported that HCV is closely related to hepatitis G, dengue, and yellow fever viruses. [14] HCV can produce at least 10 trillion new viral particles each day.

The HCV genome consists of a single, open reading frame and two untranslated, highly conserved regions, 5'-UTR and 3'-UTR, at both ends of the genome. The genome has approximately 9500 base pairs and encodes a single polyprotein of 3011 amino acids that are processed into 10 structural and regulatory proteins (see the image below).

The natural targets of HCV are hepatocytes and, possibly, B lymphocytes. Viral clearance is associated with the development and persistence of strong virus-specific responses by cytotoxic T lymphocytes and helper T cells.

In most infected people, viremia persists and is accompanied by variable degrees of hepatic inflammation and fibrosis. Findings from studies suggest that at least 50% of hepatocytes may be infected with HCV in patients with chronic hepatitis C.

The proteolytic cleavage of the virus results in two structural envelope glycoproteins (E1 and E2) and a core protein. [15] Two regions of the E2 protein, designated hypervariable regions 1 and 2, have an extremely high rate of mutation, believed to result from selective pressure by virus-specific antibodies. The envelope protein E2 also contains the binding site for CD-81, a tetraspanin receptor expressed on hepatocytes and B lymphocytes that acts as a receptor or coreceptor for HCV. HCV core protein is an important risk factor in the development of liver disease; it can modulate several signaling pathways affecting cell cycle regulation, cell growth promotion, cell proliferation, apoptosis, oxidative stress, and lipid metabolism. [16]

Other viral components are nonstructural proteins (NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, NS5B, and p7), whose proteins function as helicase-, protease-, and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, although the exact function of p7 is unknown. These nonstructural proteins are necessary for viral propagation and have been the targets for newer antiviral therapies, such as the direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs). NS2/3 and NS3/4A are proteases responsible for cleaving the HCV polyprotein. NS5A is critical for the assembly of the cytoplasmic membrane-bound replication complex; one region within NS5A is linked to an interferon (IFN) response and is called the IFN sensitivity–determining region. NS5B is an RNA dependent RNA polymerase required for viral replication; it lacks proofreading capabilities and generates a large number of mutant viruses known as quasispecies. These represent minor molecular variations with only 1%-2% nucleotide heterogeneity. HCV quasispecies pose a major challenge to immune-mediated control of HCV and may explain the variable clinical course and the difficulties in vaccine development.

Genotypes

HCV genomic analysis by means of an arduous gene sequencing of many viruses has led to the division of HCV into six genotypes based on homology. Numerous subtypes have also been identified. Arabic numerals denote the genotype, and lower-case letters denote the subtypes for lesser homology within each genotype. [13]

Molecular differences between genotypes are relatively large, and they have a difference of at least 30% at the nucleotide level. The major HCV genotype worldwide is genotype 1, which accounts for 40%-80% of all isolates. Genotype 1 also may be associated with more severe liver disease and a higher risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Genotypes 1a and 1b are prevalent in the United States, whereas in other countries, genotype 1a is less frequent. Genotype details are as follows:

-

Genotype 1a occurs in 50%-60% of patients in the United States.

-

Genotype 1b occurs in 15%-20% of patients in the United States; this type is most prevalent in Europe, Turkey, and Japan.

-

Genotype 1c occurs in less than 1% of patients in the United States.

-

Genotypes 2a, 2b, and 2c occur in 10%-15% of patients in the United States; these subtypes are widely distributed and are most responsive to medication.

-

Genotypes 3a and 3b occur in 4%-6% of patients in the United States; these subtypes are most prevalent in India, Pakistan, Thailand, Australia, and Scotland.

-

Genotype 4 occurs in less than 5% of patients in the United States; it is most prevalent in the Middle East and Africa.

-

Genotype 5 occurs in less than 5% of patients in the United States; it is most prevalent in South Africa.

-

Genotype 6 occurs in less than 5% of patients in the United States; it is most prevalent in Southeast Asia, particularly Hong Kong and Macao.

Within a region, a specific genotype may also be associated with a specific mode of transmission, such as genotype 3 among persons in Scotland who abuse injection drugs.

Etiology

Transmission

Transfusion of blood contaminated with hepatitis C virus (HCV) was once a leading means of HCV transmission. Since 1992, however, the screening of donated blood for HCV antibody sharply reduced the risk of transfusion-associated HCV infection. With the advent of more advanced screening tests for HCV such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), the risk is considered to be less than 1 per 2 million units transfused. The newer assays have decreased the window after infection to 1-2 weeks.

Persons who inject illicit drugs with nonsterile needles are at the highest risk for HCV infection. In developed countries, most of the new HCV infections are reported in injection drug users (IDUs). The most recent surveys of active IDUs in the United States indicate that approximately one third of young (aged 18–30 years) IDUs are HCV-infected. [17] Older and former IDUs typically have a much higher prevalence (approximately 70%-90%) of HCV infection, attributable to needle sharing during the 1970s and 1980s, before greater understanding of the risks of blood-borne viruses and the implementation of public educational strategies. The additional risk of acquiring hepatitis C infection from noninjection (snorted or smoked) cocaine use is difficult to differentiate from that associated with injection drug use and sex with HCV-infected partners. [17]

Transmission of HCV to healthcare workers may occur via needle-stick injuries or other occupational exposures. Needle-stick injuries in the healthcare setting result in a 3% risk of HCV transmission. According to Rischitelli et al, however, the prevalence of HCV infection among healthcare workers is similar to that of the general population. [18] Nosocomial patient-to-patient transmission may occur by means of a contaminated colonoscope, via dialysis, or during surgery, including organ transplantation before 1992.

HCV may be transmitted via sexual transmission. However, studies of heterosexual couples with discordant serostatus have shown that such transmission is extremely inefficient. [19] A higher rate of HCV transmission is noted in men who have sex with men (MSM), particularly those who practice unprotected anal intercourse and have infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). [20]

HCV may also be transmitted via tattooing, sharing razors, and acupuncture. The use of disposable needles for acupuncture, now the standard practice in the United States, should eliminate this transmission route. Maternal-fetal HCV transmission may occur at a rate of approximately 4%–5%. [21] Breastfeeding is not associated with transmission. [22] Casual household contact and contact with the saliva of those infected are inefficient modes of transmission. No risk factors are identified in approximately 10% of cases.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

The growing US opioid epidemic and its attendant rise in injection drug users (IDUs) has contributed to a more than a two-fold increase in the annual incidence rate of acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection over a decade (2004-2014), including a near four-fold increase in prescription opioid analgesic injection. [23]

HCV is the major cause of chronic hepatitis in the United States. HCV infections account for 20% of all cases of acute hepatitis and for more than 40% of all referrals to active liver clinics.

The overall prevalence of anti-HCV antibodies in the United States is 1.8% of the population. Approximately 74% of these individuals are positive for HCV RNA, meaning that active viral replication continues to occur. Thus, an estimated 3.9 million persons are infected with HCV and 2.7 million persons in the United States have chronic infection. [6] Genotype 1a occurs in 57% of patients; genotype 1b occurs in 17%.

In 2015, there were 2436 cases of acute hepatitis C reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), but this is likely an underrepresentation of the true number. [24] Alter et al reported that HCV infections account for approximately 30,000 new infections and 8,000-10,000 deaths each year in the United States. [6] Of the new infections, 60% occur in IDUs; less than 20% of new cases are acquired through sexual exposure; and 10% are due to other causes, including occupational or perinatal exposure and hemodialysis.

El-Serag et al reported that HCV was largely responsible for the increase in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States during the final decades of the 20th century. [25] In the United States, the number of deaths due to HCV-related complications increased from fewer than 10,000 in 1992 to just under 15,000 in 1999 [25] ; by 2010, there were more than 16,600 deaths attributable to HCV, [26] rising to over 19,600 such deaths in 2015. [24] According to Kim, this number is expected to increase in the future because of the current large pool of undiagnosed patients with chronic infection. [27]

International statistics

Worldwide, more than 170 million persons have hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, [28] of whom 71 million have chronic infection. [1] The Eastern Mediterranean region and Europe have the highest prevalence (2.3% and 1.5%, respectively), with other regions having an estimated prevalence of 0.5%-1.0%. [1] Jeddah City, Saudi Arabia, has a reported HCV prevalence of 0.38%. [29]

The prevalence rates in healthy blood donors are 0.01%-0.02% in the United Kingdom and northern Europe, 1%-1.5% in southern Europe, and 6.5% in parts of equatorial Africa. [30] Prevalence rates as high as 22% are reported in Egypt and are attributed to the use of parenteral antischistosomal therapy. [3]

Race-, sex-, and age-related differences in incidence

In the United States, HCV infection is more common among minority populations, such as black and Hispanic persons in association with lower economic status and educational levels. In addition, in the United States, genotype 1 is more prevalent in black individuals than in other racial groups.

Racial disparity has also been reported in the all-cause mortality in patients with HCV infection. A 2017 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III report found that having chronic HCV was associated with a 2.63-fold higher all-cause mortality rate ratio (MRR) compared with being HCV negative. [31] The highest MRR of having chronic HCV compared to being HCV negative was 7.48 among Mexican Americans, 2.67 among non-Hispanic white persons, and 2.02 among non-Hispanic black persons. Mexican Americans with chronic HCV had approximately a seven-fold higher mortality than HCV-negative individuals. [31]

No sex preponderance occurs with HCV infection. [6]

In the United States, 65% of people with HCV infection are aged 30-49 years. Those who acquire the infection at a younger age have a somewhat better prognosis than those who are infected later in life. Infection is uncommon in persons aged 20 years and younger but is more prevalent in persons older than 40 years. [32, 33] Data suggest that an association exists between age and transmission route, such as nonsterile medical procedures, including vaccination and parenteral drug treatment. [34]

A 2022 CDC report noted a 2019 incidence of 0.1 per 100,000 population of HCV infection in those younger than 20 years. [35]

Prognosis

Infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) is self-limited in 15% to 50% of patients. [1, 17, 36, 37] In a review of HCV infection, it was reported that chronic infection developed in 70-80% of patients. [13] Cirrhosis develops within 20 years of disease onset in 20% of persons with chronic infection. [38] The onset of chronic hepatitis C infection early in life often leads to less serious consequences. [33, 34] Hepatitis B virus (HBV) coinfection, iron overload, and alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency may promote the progression of chronic HCV infection to HCV-related cirrhosis. [36, 37] The INSIGHT Study reported the three most common comorbidities with HCV across 9 Asia-Pacific countries were cirrhosis, hypertension, and diabetes. [2]

Two studies of compensated cirrhosis in the United States and Europe showed that decompensation occurred in 20% of patients and that hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) occurred in approximately 10% of patients. [39, 40] The survival rate at 5 and 10 years was 89% and 79%, respectively. HCC develops in 1-4% of patients with cirrhosis each year, after an average of 30 years.

The risk of cirrhosis and HCC doubles in patients who acquired HCV infection via transfusion. [41] Progression to HCC is more common in the presence of cirrhosis, alcoholism, and HBV coinfection.

Bellentani et al [42] and Hourigan et al [43] reported that the rate and likelihood of disease progression is influenced by alcohol use, immunosuppression, sex, iron status, concomitant hepatitis, and age of acquisition.

In an observational study of Veterans Affairs (VA) HCV clinical registry data on 128,769 patients, McCombs et al found that those who achieved an undetectable HCV viral load had a decreased risk of subsequent liver morbidity and death. [44, 45] Viral load suppression reduced the risk for future liver events by 27% (eg, compensated/decompensated cirrhosis, HCC, or liver-related hospitalization), as well as reduced the risk of death by 45%, relative to patients who did not achieve viral load suppression. [44, 45] Additionally, patient race/ethnicity and HCV genotypes affected the risk of future liver events and death. The risk for all liver events and death was higher in white patients relative to black patients, and those with HCV genotype 3 had a higher risk for all study outcomes compared to patients who had HCV genotype 2 (lowest risk) or genotype 1. [44, 45]

Patient Education

Patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection should be advised to abstain from alcohol use, as it accelerates the onset of cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease. Patients should be informed about the low but present risk for transmission to sex partners. Optimally, patients should use barrier protection during sexual intercourse. [46] Sharing personal items that might have blood on them, such as toothbrushes or razors, should be avoided.

Patients with hepatitis C should not donate blood or organs. One exception is in patients with HCV who require liver transplantation. Arenas et al showed that liver transplant recipients who received liver grafts from HCV-positive donors had 5-year survival rates comparable to recipients who received grafts from HCV-negative donors. [47] Given the shortage of organs and the long waiting list, this strategy has proven safe and effective.

Patients should also check with a healthcare professional before taking any new prescription pills, over-the counter drugs, or supplements, as these can potentially damage the liver.

-

Hepatitis C. Causes of chronic liver disease. Courtesy of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

-

Hepatitis C viral genome. Courtesy of Hepatitis Resource Network.

-

Natural history of hepatitis C virus infection.

-

Diagnostic algorithm for hepatitis C virus infection.

-

Evolution of the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection.

-

Pegylated interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C.

-

Cold agglutinin disease indistinguishable from cryoglobulinemia. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Cryoglobulinemia, palpable purpura, dysproteinemic purpura, and leukocytoclastic vasculitis (small vessel vasculitis). Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Cutis marmorata. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Erythema multiforme, bull's-eye lesions. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Erythema dyschromicum perstans. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Erythema dyschromicum perstans. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Erythema nodosa. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Erythema nodosa. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Erythema multiforme. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Erythema multiforme. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Erythema multiforme. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Erythema multiforme of the oral mucosa. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Erythema multiforme (Stevens-Johnson syndrome). Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Palmar erythema. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Granuloma annulare. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Disseminated superficial (actinic) porokeratosis. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Disseminated superficial (actinic) porokeratosis. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Lichen planus. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Lichen planus. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Lichen planus. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Lichen planus (hypertrophic type). Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Lichen planus (oral lesions). Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Lichen planus (volar wrist). Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Lymphoma cutis. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Palpable purpura. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Purpura in hemophilia (factor VIII deficiency). All ecchymoses and bland petechiae are in the differential diagnosis of thrombocytopenic purpuras, including thrombocytopenia secondary to hepatitis C virus in which an autoantibody to platelets is present. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Progressive pigmented purpuric eruption. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Progressive pigmented purpura (photo rotated 90°). Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Progressive pigmented purpura (Gougerot-Blum disease). Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Progressive pigmented purpura (Schamberg disease). Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Thrombocytopenic purpura. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Prurigo nodularis. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Prurigo nodularis. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Prurigo nodularis. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Chronic urticaria. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Urticaria (secondary to penicillin). Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Nodular vasculitis. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Henoch-Schönlein purpura, palpable purpura, and leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Vitiligo. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Vitiligo. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

-

Waldenström hypergammaglobulinemic purpura. Courtesy of Walter Reed Army Medical Center Dermatology.

Tables

What would you like to print?

- Overview

- Presentation

- DDx

- Workup

- Treatment

- Approach Considerations

- Interferons and Pegylated Interferons

- Interferons and Ribavirin

- Direct-Acting Antiviral Agents (DAAs)

- Management and Monitoring of Acute HCV Infection

- AASLD/IDSA Simplified Pangenotypic HCV Treatment

- Treatment-Naive Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C Infection

- Treatment-Experienced Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C Infection

- Decompensated Cirrhosis

- HIV-HCV Coinfection

- HBV-HCV Coinfection

- HCV Recurrence After Liver Transplantation

- HCV-Uninfected Transplant Recipients With Organs From HCV-Viremic Donors

- HCV and Renal Impairment or Kidney Transplant

- HCV and Pregnancy

- HCV and Children (2023 CDC and 2024 AASLD/IDSA Guidelines)

- Patients Using Alcohol or Injection Drugs

- HCV and Men Who Have Sex With Men

- Deterrence/Prevention

- Consultations and Long-Term Monitoring

- Show All

- Medication

- Media Gallery

- References