Practice Essentials

Acute bronchitis is a clinical syndrome produced by inflammation of the trachea, bronchi, and bronchioles. In children, acute bronchitis usually occurs in association with viral lower respiratory tract infection. Acute bronchitis is rarely a primary bacterial infection in otherwise healthy children. (See Pathophysiology, as well as Etiology.)

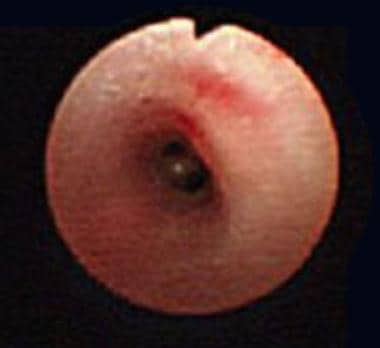

Examples of normal airway color and architecture and an airway in a patient with chronic bronchitis are shown below.

Airway of a child with chronic bronchitis shows erythema, loss of normal architecture, and swelling.

Airway of a child with chronic bronchitis shows erythema, loss of normal architecture, and swelling.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of acute bronchitis usually include productive cough and sometimes retrosternal pain during deep breathing or coughing. Generally, the clinical course of acute bronchitis is self-limited, with complete healing and full return to function typically seen within 10-14 days following symptom onset. (See Clinical Presentation.)

Chronic bronchitis is due to recurrent inflammation that may be associated with active infection resulting in degenerative changes within the bronchial tubes. Patients with chronic bronchitis have more mucus than normal because of either increased production or decreased clearance. Coughing is the mechanism by which excess secretions are cleared.

Chronic bronchitis is often associated with asthma, cystic fibrosis, dyskinetic cilia syndrome, foreign body aspiration, or exposure to an airway irritant. Recurrent tracheobronchitis may occur with tracheostomies or immunodeficiency states.

Defining chronic bronchitis and its prevalence in childhood has been complicated by the significant clinical overlap with asthma and reactive airway disease states. In adults, chronic bronchitis is defined as daily production of sputum for at least 3 months in 2 consecutive years. Some have applied this definition to childhood chronic bronchitis. Others limit the definition to a productive cough that lasts more than 3-4 weeks despite medical therapy.

Chronic bronchitis has also been defined as a complex of symptoms that includes cough that lasts more than 1 month or recurrent productive cough that may be associated with wheezing or crackles on auscultation. Elements of these descriptors are present in the working definitions of asthma, as well. [1]

Management

Treatment of chronic bronchitis in pediatric patients includes rest, use of antipyretics, adequate hydration, and avoidance of smoke. (See Treatment.)

Analgesics and antipyretics target the symptoms of pediatric bronchitis. In chronic cases, bronchodilator therapy should be considered. Oral corticosteroids should be added if cough continues and the history and physical examination findings suggest a wheezy form of bronchitis. (See Medication.)

Pathophysiology

Acute bronchitis leads to the hacking cough and phlegm production that often follows upper respiratory tract infection. This occurs because of the inflammatory response of the mucous membranes within the lungs' bronchial passages. Viruses, acting alone or together, account for most of these infections. [2, 3]

In children, chronic bronchitis follows either an endogenous response (eg, excessive viral-induced inflammation) to acute airway injury or continuous exposure to certain noxious environmental agents (eg, allergens or irritants). An airway that undergoes such an insult responds quickly with bronchospasm and cough, followed by inflammation, edema, and mucus production. This helps explain the fact that apparent chronic bronchitis in children is often actually asthma.

Mucociliary clearance is an important primary innate defense mechanism that protects the lungs from the harmful effects of inhaled pollutants, allergens, and pathogens. [4] Mucociliary dysfunction is a common feature of chronic airway diseases.

The mucociliary apparatus consists of 3 functional compartments: the cilia, a protective mucus layer, and an airway surface liquid (ASL) layer, which work together to remove inhaled particles from the lung. Animal study data have identified a critical role for ASL dehydration in the pathogenesis of mucociliary dysfunction and chronic airway disease. [5] ASL depletion resulted in reduced mucus clearance and histologic signs of chronic airway disease, including mucous obstruction, goblet cell hyperplasia, and chronic inflammatory cell infiltration. Study animals experienced reduced bacterial clearance and high pulmonary mortality as a result.

The role of irritant exposure, particularly cigarette smoke and airborne particulates, in recurrent (wheezy) bronchitis and asthma is becoming clearer. Kreindler et al demonstrated that the ion transport phenotype of normal human bronchial epithelial cells exposed to cigarette smoke extract is similar to that of cystic fibrosis epithelia, in which sodium is absorbed out of proportion to chloride secretion in the setting of increased mucus production. [6] These findings suggest that the negative effects of cigarette smoke on mucociliary clearance may be mediated through alterations in ion transport.

McConnell et al noted that organic carbon and nitrogen dioxide airborne particulates were associated with the chronic symptoms of bronchitis among children with asthma in southern California. [7]

A chronic or recurrent insult to the airway epithelium, such as recurrent aspiration or repeated viral infection, may contribute to chronic bronchitis in childhood. Following damage to the airway lining, chronic infection with commonly isolated airway organisms may occur. The most common bacterial pathogen that causes lower respiratory tract infections in children of all age groups is Streptococcus pneumoniae. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis may be significant pathogens in preschoolers (age < 5 y), whereas Mycoplasma pneumoniae may be significant in school-aged children (ages 6-18 y).

Children with tracheostomies are often colonized with an array of flora, including alpha-hemolytic streptococci and gamma-hemolytic streptococci. With acute exacerbations of tracheobronchitis in these patients, pathogenic flora may include Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus (including methicillin-resistant strains), among other pathogens. Children predisposed to oropharyngeal aspiration, particularly those with compromised protective airway mechanisms, may become infected with oral anaerobic strains of streptococci.

Etiology

Acute bronchitis is generally caused by respiratory infections; approximately 90% are viral in origin, and 10% are bacterial. Chronic bronchitis may be caused by repeated attacks of acute bronchitis, which can weaken and irritate bronchial airways over time, eventually resulting in chronic bronchitis. Industrial pollution is also a common cause; however, the chief culprit is heavy long-term cigarette smoke exposure.

Viral infections include the following:

-

Adenovirus

-

Influenza

-

Parainfluenza

-

Respiratory syncytial virus

-

Rhinovirus

-

Coxsackievirus

-

Herpes simplex virus

Secondary bacterial infection as part of an acute upper respiratory tract infection is extremely rare in non–smoke-exposed patients without cystic fibrosis or immunodeficiency but may include the following:

-

S pneumoniae

-

M catarrhalis

-

H influenzae (nontypeable)

-

Chlamydia pneumoniae (Taiwan acute respiratory [TWAR] agent)

-

Mycoplasma species

Air pollutants, such as those that occur with smoking and from second-hand smoke, also cause incident bronchiolitis. [11] Tsai et al demonstrated that in utero and postnatal household cigarette smoke exposure is strongly linked to asthma and recurrent bronchitis in children. [12] A study by Ghosh et al suggested that two single-nucleotide polymorphisms (rs2228001 and rs2733532) on the DNA repair gene XPC are linked to induction of the pathogenesis of bronchitis by air pollution in children aged 2 years or younger, with the two polymorphisms specifically interacting with particulate matter of less than 2.5 μm. [13]

Other causes include the following:

-

Allergies

-

Chronic aspiration or gastroesophageal reflux

-

Fungal infection

Protracted bacterial bronchitis (chronic wet cough)

A subset of children with a chronic productive cough have a significant bacterial cause underlying their symptoms. Various terms have been used for these conditions, including protracted bacterial bronchitis or chronic wet cough. While the clinical criteria for establishing this diagnosis are somewhat nonspecific, it is characterized by cough that persists for at least 4 weeks, lacking features suggesting an alternative explanation, and resolves following 2-4 weeks of antimicrobial therapy. [14] Protracted bacterial bronchitis (PBB) is common among pediatric populations, affecting up to 40% of children newly referred for specialist management of persistent wet cough. [15] It is speculated that an initial viral infection disrupts respiratory epithelial and ciliary function, leading to chronic inflammation supporting the formation of bacterial biofilms. If untreated, protracted bacterial bronchitis may lead to chronic suppurative lung disease or bronchiectasis. [16]

The diagnosis is established by flexible bronchoscopy of the lower airways demonstrating edema, increased bronchial secretions, and positive bacterial culture following bronchoalveolar lavage. Marsh et al (2019) demonstrated that bacterial biomass, neutrophil percentage, interleukin (IL)–8, and IL-1-beta levels were significantly higher in children with protracted bacterial bronchitis undergoing bronchoalveolar lavage when compared with controls. [17] A multicenter study of patients undergoing bronchoalveolar lavage demonstrated that Streptococcus pneumoniae, nontypable Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis were the predominant infecting flora. [18] Most children with PBB will experience the resolution of cough following initial antibiotic treatment; however, up to 44% will have more than three episodes in the year following diagnosis and 16% will progress to bronchiectasis within 2 years. [19] Both the American College of Chest Physicians [20] and the European Respiratory Society [21] statements on protracted bacterial bronchitis recommend treatment with an appropriate antibiotic for 3-4 weeks. Further investigation (chest CT, immunologic testing) is advised for those patients who do not experience improvement in symptoms.

Plastic bronchitis

Plastic bronchitis is an unusual but potentially devastating form of obstructive bronchial disease. The disease is characterized by the development of arborizing, thick, tenacious casts of the tracheobronchial tree that produce airway obstruction. [22, 23] In one study of 34 patients with plastic bronchitis, 24 had single-ventricle congenital heart disease, 9 had primary pulmonary disease, and one had no underlying disease. [24]

Patients with congenital heart disease with single-ventricle physiology who have undergone a Fontan operation are a group at higher risk for development of this condition, for unknown reasons. In some cases, plastic bronchitis appears many years after the Fontan procedure is performed. [25] Zahorec et al describe cases occurring in the immediate postoperative period following a Fontan procedure. These patients were successfully managed with short periods of high-frequency jet ventilation and vigorous pulmonary toilet. [26]

Therapies include endoscopic debridement of the airway, vigorous pulmonary toilet, and aerosolized heparin or tissue plasminogen activator. For some, nebulized anticholinergic medication and compression vest chest physiotherapy have been helpful. [27] Shah et al performed thoracic duct ligation, resulting in complete resolution of the formation of casts in 2 patients with plastic bronchitis refractory to medical management. [28] DePopas et al (2017) describe 3 cases in which percutaneous thoracic duct intervention resulted in significant to complete resolution of symptoms associated with recurrent cast formation. [29] Lymphatic embolization and stent grafting represent additional treatment options. [30] These results suggest that high intrathoracic lymphatic pressures are related to the development of the recurrent bronchial casts seen in this disorder.

Epidemiology

Data collected from the National Ambulatory Care Survey 1991 Summary showed that 2,774,000 office visits by children younger than 15 years resulted in a diagnosis of bronchitis. [31] Although the report did not separate diagnoses into acute and chronic bronchitis, the frequency of visits made bronchitis just slightly less common than otitis media and slightly more common than asthma. However, in children, asthma is often underdiagnosed and is frequently misdiagnosed as chronic or recurrent bronchitis. Since 1996, 9-14 million Americans have been diagnosed with chronic bronchitis annually.

Bronchitis, both acute and chronic, is prevalent throughout the world and is one of the top 5 reasons for childhood physician visits in countries that track such data. The incidence of bronchitis in British schoolchildren is reported to be 20.7%.

Weigl et al noted an overall increase in hospitalization for lower respiratory tract infection (laryngotracheobronchitis, bronchitis, wheezing bronchitis, bronchiolitis, bronchopneumonia, pneumonia) among German children from 1996 to 2000; this is consistent with observations among children from the United States, United Kingdom, and Sweden. [32] The incidence rate of bronchitis in children in this German cohort was 28%.

A study by Berhane et al indicated that as a result of improvements in ambient air quality in Southern California, bronchitic symptoms decreased in that region’s children between 1993 and 2012. [33, 34]

Differences in population prevalences have been identified in patients with chronic bronchitis. For example, because of the association of chronic bronchitis with asthma and the concentration of asthma risk factors among inner-city populations, this population group is at higher risk.

The incidence of acute bronchitis is equal in males and females. The incidence of chronic bronchitis is difficult to state precisely because of the lack of definitive diagnostic criteria and the considerable overlap with asthma. However, in recent years, the prevalence of chronic bronchitis has been reported to be consistently higher in females than in males.

Acute (typically wheezy) bronchitis occurs most commonly in children younger than 2 years, with another peak seen in children aged 9-15 years. Chronic bronchitis affects people of all ages but is more prevalent in persons older than 45 years.

Prognosis

Acute bronchitis is almost always a self-limited process in the otherwise healthy child. However, it frequently results in absenteeism from school and, in older patients, work. Chronic bronchitis is manageable with proper treatment and avoidance of known triggers (eg, tobacco smoke). Proper management of any underlying disease process, such as asthma, cystic fibrosis, immunodeficiency, heart failure, bronchiectasis, or tuberculosis, is also key. These patients need careful periodic monitoring to minimize further lung damage and progression to chronic irreversible lung disease.

A long-term prospective study found that children who had bronchitis at least once before the age of 7 years were more likely to have been diagnosed with asthma and pneumonia by age 53 years. The association with asthma and pneumonia in adulthood was strongest for participants who had a history of recurrent-protracted childhood bronchitis. [35]

An analysis of data from a nationwide British cohort study showed that children who had a lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) such as bronchitis by the age of 2 years were 93% more likely to die of respiratory disease by age 73 years than children who had not had a LRTI by age 2 years. The rate of premature adult death caused by respiratory disease was a 2.1% among those who had a LRTI during early childhood, versus 1.1% among those who did not report a LRTI before age 2 years. [36]

Complications

Complications are extremely rare and should prompt evaluation for tracheobronchial aspiration, anomalies of the respiratory tract, or immunodeficiency. Complications may include the following:

-

Bronchiectasis

-

Bronchopneumonia

-

Acute respiratory failure

Patient Education

Instruct older patients regarding the need for immunization against pertussis, diphtheria, and influenza, which reduces the risk of bronchitis due to the causative organisms. Instruct these patients to avoid passive environmental tobacco smoke; to avoid air pollutants, such as wood smoke, solvents, and cleaners; and to obtain medical attention for prolonged respiratory infections.

Instruct parents that children may attend school or daycare without restrictions except during episodes of acute bronchitis with fever. Also instruct parents that children may return to school or daycare when signs of infection have decreased, appetite returns, and alertness, strength, and a feeling of well-being allow.

-

Normal airway color and architecture (in a child with mild tracheomalacia).

-

Airway of a child with chronic bronchitis shows erythema, loss of normal architecture, and swelling.