Practice Essentials

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a rheumatic disease characterized by autoantibodies directed against self-antigens, immune complex formation, and immune dysregulation, resulting in damage to essentially any organ. The disease can affect, for example, the kidneys, skin, blood cells, and nervous system. (See the image below.) The natural history of SLE is unpredictable; patients may present with many years of symptoms or with acute, life-threatening disease. Because of its protean manifestations, lupus must be considered in the differential diagnoses of many conditions, including fevers of unknown origin, arthralgia, anemia, new-onset kidney disease, psychosis, and fatigue. Early diagnosis and careful treatment tailored to individual patient symptoms have improved the prognosis in what was once perceived as an often-fatal disease.

The classic malar rash, also known as a butterfly rash, with distribution over the cheeks and nasal bridge. Note that the fixed erythema, sometimes with mild induration as seen here, characteristically spares the nasolabial folds.

The classic malar rash, also known as a butterfly rash, with distribution over the cheeks and nasal bridge. Note that the fixed erythema, sometimes with mild induration as seen here, characteristically spares the nasolabial folds.

Signs and symptoms of pediatric SLE

The most frequent presenting symptoms of SLE are prolonged fever and malaise, with evidence of multisystem involvement. Children often have a history of fatigue, joint pain, rash, and fever. However, children may also present with various acute symptoms, including memory loss, psychosis, transverse myelitis, hemoptysis, edema of the lower extremities, headache, and painful mouth sores.

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis of pediatric SLE

Laboratory studies

The initial laboratory evaluation should include a complete blood count (CBC) with platelets and reticulocyte count; a complete chemistry panel to evaluate electrolytes, liver, and kidney function; urine analysis; and a measure of acute phase reactants (eg, erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR] or C-reactive protein [CRP]). Diagnostic laboratory studies include antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti–double-stranded DNA, anti-Smith antibody, lupus anticoagulant, and antiphospholipid antibody panel.

Imaging studies

Chest radiographs and electrocardiograms should be obtained. Other imaging studies should be guided by clinical manifestations.

See Workup for more detail.

Management of pediatric SLE

The most important tool in the care of the patient with SLE is careful and frequent clinical and laboratory evaluation to tailor the medical regimen and to provide prompt recognition and treatment of disease flares. Consideration should be given to the prevention of atherosclerosis and osteoporosis, because these are long-term consequences of SLE and its treatment.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

The first written description of lupus dates to the 13th century. Rogerius named the disease using the Latin word for wolf, because the cutaneous manifestations he described appeared similar to those of a wolf bite. Osler was the first physician who recognized that systemic features of the disease could occur without skin involvement. [1] Diagnosis was made easier with the discovery of lupus erythematosus (LE) cells in 1948. In 1959, the presence of anti ̶ deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) antibodies was noted. The use of the New Zealand black/white mouse model, which manifested spontaneous Coombs-positive anemia and many other manifestations of lupus, has allowed intensive study of SLE’s mechanisms and the importance of immunosuppressive therapy.

The use of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) in the 1950s resulted in amelioration of disease manifestations. The replacement of ACTH using corticosteroids improved treatment, with improvement in 5-year survival from 5% to 70%. The substantial adverse effects of corticosteroids led to a strategy of using various immunosuppressive drugs to minimize the need for corticosteroids, improving the prognosis for patients. For children with renal disease, recognition of the steroid-sparing effect of immunosuppressive agents, such as azathioprine, mycophenolate, and cyclophosphamide, has greatly improved kidney organ survival and outcome. (See Treatment and Medications.)

Advances in treatment using targeted biological therapies may further improve treatment outcomes. As patients continue to improve and survive, physicians now must assess patients for long-term disease sequelae, such as atherosclerosis, and develop prevention strategies. Strategies using genomics and proteomics give hope for identification of biomarkers that can be used for early disease detection and treatment. [2]

Etiology

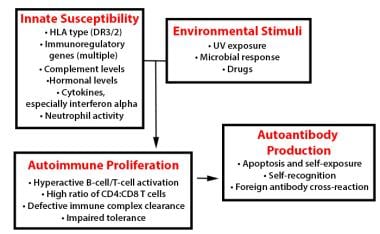

The specific causes of systemic lupus erythematosus remain undefined. Research suggests that many factors, including genetics, hormones, and the environment (eg, sunlight, drugs), contribute to the immune dysregulation observed in lupus. (See the diagram below.)

In systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), many genetic-susceptibility factors, environmental triggers, antigen-antibody responses, B-cell and T-cell interactions, and immune clearance processes interact to generate and perpetuate autoimmunity.

In systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), many genetic-susceptibility factors, environmental triggers, antigen-antibody responses, B-cell and T-cell interactions, and immune clearance processes interact to generate and perpetuate autoimmunity.

Within the healthy population, a subset of individuals has small amounts of low-titer antinuclear antibody (ANA) or other autoantibody such as anti-Ro(SSA), anti-La(SSB), or antithyroid antibodies. In lupus, increased production of specific autoantibodies (anti-dsDNA, anti-RNP, and anti-Smith antibodies) leads to immune complex formation and tissue damage from direct binding in tissues, immune complex deposition in tissues, or both.

Evidence suggests that people with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) have antigen-specific antibody responses to DNA, other nuclear antigens, ribosomes, platelets, erythrocytes, leukocytes, and tissue-specific antigens. The resulting immune complexes cause widespread tissue damage. Cell-mediated autoimmune responses also play a pathophysiologic role.

Autoantibody production, by relatively few B lymphocytes, may be a byproduct of polyclonal B-cell activation in which many more B lymphocytes are activated, perhaps not in response to specific antigenic stimuli. Data on 3 adolescents with lupus demonstrated a high percentage of mature naive B cells (25-50% vs 5-20% in healthy adolescents) producing self-reactive antibodies even before they participated in an immune response, suggesting defective checkpoints in B-cell development. [3]

The discovery of virallike particles in lymphocytes in patients with lupus led to the theory that viral infection causes polyclonal activation in lupus. However, these particles may simply be breakdown products of intracellular materials. This assumption was supported by evidence in which specific viruses, such as Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus, in lupus white blood cells (WBCs), were not isolated in polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay. Thus, positive titers to infectious agents in patients with lupus may be another manifestation of nonspecific polyclonal activation of B cells, an important point during initial evaluation and diagnosis. However, viral stimulation of the innate immune system (dendritic cells), coupled with genetic defects in the innate and adaptive immune responses, could lead to loss of tolerance and increasingly specific autoantibody formation.

The presence of measurable autoantibodies implies a loss of tolerance to self-antigens and may include T-lymphocyte abnormalities. Early studies suggested a loss of T-suppressor function; however, subsequent investigations have centered on defects of programmed cell death, or apoptosis. This process of programmed cell death may be dysregulated in lupus, resulting in cells with the potential for self-reactivity persisting instead of undergoing the normal process of apoptosis.

T cells from patients with lupus have been found with increased levels of Bcl-2, a protein that delays apoptosis. Patients have also been found to have lymphocytes that underwent increased apoptosis. One explanation may be that in lupus, lymphocytes that make self-reactive antibodies survive in the host but undergo increased cell turnover after an inciting trigger, such as a viral infection, begins the process that manifests as lupus.

Over the past 15 years, studies of lupus have implicated the importance of innate immunity. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells are decreased in the blood of lupus patients but are found in high concentration at sites of inflammation such as the kidney and skin, secreting alpha-interferons. [4] The presence of high concentrations of interferon in the sera of lupus patients was originally described by Lars Ronnblom and was a seminal observation of lupus pathophysiologic mechanisms. [5]

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells endocytose immune complexes and nucleic debris through the Fc gamma-receptor IIa, activating toll-like receptors 7 and 9 and triggering production of interferon-alpha and other proinflammatory cytokines. The excess necrotic and apoptotic materials are due to ultraviolet damage, viral infection, and genetic differences, some of which are listed below and which include impaired clearance of these materials. Necrotic materials are also due to neutrophil responses to infection. Neutrophils can extrude their nuclear materials to form neutrophil extracellular traps or NETosis, immobilizing bacteria and fungi. NETosis triggers an interferon signal and plasmacytoid dendritic cell activation that can induce lupus. [6]

Other immunologic mechanisms may also be important, including defects in macrophage phagocytic activity or handling of immune complexes. In addition, deficiencies of complement components, including C4, C2, and C1q, have been associated with lupus, likely due to defective clearance of immune complexes.

Complement receptors may be abnormal in some patients, leading to problems with clearance of immune complexes and subsequent deposition into tissues. This may, in association with dyslipoproteinemia, lead to significant vascular complications.

The predominance of lupus in females suggests sex hormones may play a role in autoimmune diseases. Research found that patients with lupus did not have different serum levels of estrogen and prolactin than did controls; however, free androgen was lower, whereas follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) levels were higher in postpubertal boys and girls with SLE.

Drugs, such as anticonvulsants and antiarrhythmic agents, can also play a role in the pathogenesis of lupus. These drugs can cause a lupuslike syndrome, which resolves when the drug is discontinued or can be implicated as the trigger in systemic lupus. Sun exposure leading to inflammation and apoptosis of skin cells can also trigger systemic lupus.

Genetic susceptibility

The use of microarray technology to detect candidate susceptibility genes has led to the identification of several potential gene-risk candidates, including the P-selectin gene (SELP), the interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 gene (IRAK1), PTPN22, and the interleukin-16, protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type T, toll-like receptor (TLR) 8, and CASP 10 genes. [7, 8, 9]

Enhanced Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7) signaling has been suggested as a mechanism of systemic autoimmune disease. Brown et al identified a previously undescribed single-point missense gain-of-function TLR7 mutation, TLR7Y264H, in a child with severe SLE and subsequently found it in other patients with severe SLE. When introduced into mice, the TLR7Y264H variant caused lupus. [10]

Epidemiology

In the United States, the incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) varies by location and ethnicity. Incidence rates among children younger than age 15 years have been reported to be 0.5-0.6 case per 100,000 persons. Prevalence rates of 4-250 cases per 100,000 persons have been reported, with greater prevalence in Native Americans, Asian Americans, Latin Americans, and African Americans. In one study of adults, the incidence of lupus in African American females was estimated at 1 in 500. African American children may represent up to 60% of patients younger than 20 years with lupus. In the pediatric population, just under 60% of cases are seen in patients of African American ethnicity. However, lupus does occur in persons of every ethnic and racial background.

Prevalence rates are higher in females than in males. A female-to-male ratio of approximately 4:1 occurs before puberty and after menopause, with a ratio of 8:1 between onset and loss of estrogen cycles.

Approximately 20% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus initially present by the second decade of life. Disease onset has been reported as early as the first year of life. However, SLE remains uncommon in children younger than age 8 years.

Prognosis

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a high-risk disease with the possibility of end-organ damage to any vital or nonvital organ. This damage can severely affect organ function and can lead to decreased quality of life.

In addition, the treatment of SLE is fraught with potential complications from the adverse effects of steroids, infection from immunosuppression and poorly controlled disease, and cardiovascular disease leading to early myocardial infarction.

Pregnancy can also complicate SLE, increasing the risk of renal disease, thrombophlebitis, and disease flare. The infant is at risk for being small for gestational age (SGA) and for neonatal lupus.

Current mortality figures suggest that patients have a 95% rate of survival at 5 years. Some clinicians report a 98-100% survival rate at 5 years. These figures depend on disease severity and compliance with therapy. Mortality rates rise over time, with the major causes of death being infection, nephritis, central nervous system (CNS) disease, pulmonary hemorrhage, and myocardial infarction. One indicator of morbidity and mortality risk is frequency of emergency department visits.

A study by Rees et al that estimated SLE mortality from 1999-2012 reported that young people with SLE had the greatest relative risk of death. The mortality rate ratio was 3.81 (95% CI 1.43, 10.14) in those under 40 years of age compared to the control group. [11]

The 5-year survival rate for children with SLE is more than 90%. Most deaths in children with SLE are the result of infection, nephritis, renal failure, neurologic disease, or pulmonary hemorrhage. Myocardial infarction may occur in the young adult years as a complication of persisting inflammation and, possibly, long-term corticosteroid use.

Complications

Children with lupus may have hematologic abnormalities, including hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, or lymphopenia. Patients with immune complex disease in the kidneys may present with nephritis or nephrotic syndrome. Numerous neurologic abnormalities, from psychosis and seizure to cognitive disorders to peripheral neuropathies, may also occur. Their exact relationship to the presence of immune complexes and autoantibodies remains unclear.

A study by Giani et in the United Kingdom found that 25% of patients with juvenile-onset SLE had neuropsychiatric involvement within 5 years of diagnosis. The most common neurologic manifestations were headaches, mood disorders, cognitive impairment, anxiety, seizures, movement disorders, and cerebrovascular disease. [12]

Pulmonary disease manifests as pulmonary hemorrhage, fibrosis, or infarct. Various rashes, gastrointestinal (GI) manifestations, serositis, arthritis, endocrinopathies, and cardiac abnormalities (eg, valvulitis and carditis) are observed. No organ is spared from the effects of this multisystem disease. However, the clinical presentation widely varies. How the clinical manifestations depend on the underlying specific immunologic disarray in a particular patient remains to be determined and is the focus of intense study.

Patient Education

The patient and his or her family must have a thorough understanding of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), its potential severity, and the complications of the disease and its therapy.

Treatment is difficult, especially for adolescent patients. The physician and parents should expect issues, including depression and noncompliance, to arise. The best method for deterrence is to thoroughly educate the patient and family through discussion, support groups, and literature.

Educate all patients with SLE with regard to the serious complications possible from unplanned pregnancy, poor compliance, recreational drug use, and infection, including with sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). Poor compliance, in particular, is a significant prognostic factor.

For patient education information, see Lupus (Systemic Lupus Erythematosus), Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS), and Chronic Pain.

-

The classic malar rash, also known as a butterfly rash, with distribution over the cheeks and nasal bridge. Note that the fixed erythema, sometimes with mild induration as seen here, characteristically spares the nasolabial folds.

-

In systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), many genetic-susceptibility factors, environmental triggers, antigen-antibody responses, B-cell and T-cell interactions, and immune clearance processes interact to generate and perpetuate autoimmunity.